The music staff, made up of five parallel horizontal lines, is one of the foundations of music theory—a notation system used to write and read Western music.

Lines and Spaces of the Music Staff (or Stave)

The gaps between the lines are called spaces. Musical notes are placed either on the lines or in the spaces.

Both lines and spaces are always counted from bottom to top:

In addition to notes, the music staff also contains other musical symbols such as clefs (treble, bass, alto), rests (whole rest, half rest, quarter rest…), and accidentals (sharp, flat, natural…).

Ledger Lines

To write notes that go beyond the range of the standard five lines, music notation uses ledger lines, which are short lines sized to match the width of the note they support.

These small lines are added above the staff for higher-pitched notes, and below the staff for lower-pitched ones. This extends the staff’s range according to the instrument or the singer’s voice, allowing each pitch to be notated precisely.

In the video below, notice the ledger lines. Specifically, the first three notes below the upper staff (A, B, and C) and the last three notes above the lower staff (also A, B, and C) are all written on ledger lines.

Other Types of Staves

Traditionally, Gregorian chant notation uses a four-line staff.

For single-pitch percussion instruments—such as drums, cymbals, castanets, or triangles—where only rhythm is notated, a single-line staff is typically used.

Clefs (Treble, Bass, Alto)

To determine the name of each musical note on the staff, one of three musical clefs is placed at the beginning of the staff:

- The treble clef is placed on the second line.

- The bass clef is placed on the third or fourth line.

- The alto clef (also called C clef) can be placed on the first, second, third, or fourth line.

Once the name of a note is established using one of the three clefs, the names of the other notes follow the order of the musical scale.

For example, with the treble clef:

Musical Rests

In music and music theory, a rest—such as a whole rest, half rest—is a musical symbol placed on the staff. It indicates a temporary break in sound and contributes to the rhythm of the notes.

Musical Accidentals

Musical accidentals—sharp, flat, natural, double sharp, and double flat—are symbols used to raise or lower the pitch of a note by one or two semitones. They are also written on the staff: either at the beginning of the piece, right after the clef (called key signature accidentals), or directly in front of a note.

A Brief History of the Music Staff

While the five-line staff may seem like an obvious choice today, its invention was a revolutionary development that took centuries to take shape. Understanding its origins helps to better grasp its fundamental importance in Western music.

Notation by Neumes

In the early Middle Ages, music, especially Gregorian chant, was notated using neumes. These symbols, placed above the liturgical text, indicated the melodic contour (whether the melody ascended or descended) but did not specify the exact pitch or intervals of the notes. This system, known as in campo aperto (in open field), relied entirely on the memory of the cantor, who was already expected to know the melody.

The Invention of Guido d’Arezzo in the 11th Century

A pivotal breakthrough came in the early 11th century with the Italian Benedictine monk Guido d’Arezzo (c. 992–1050). To address the imprecision of the neumes, he systematized the use of horizontal lines, with each line representing a fixed and identifiable pitch. This fundamental innovation established him as the inventor of the modern music staff.

How Many Lines at First?

Guido d’Arezzo initially established a four-line staff, known as the tetrachord. Used as the standard for Gregorian chant, it is still in use today.

It was the addition of a clef (Do or Fa) to establish a reference pitch that made sight-reading possible. This invention is said to have reduced the training time for a cantor from ten years to less than one year.

The Evolution Toward the Five-Line Staff

With the development of polyphony and instrumental music in the following centuries, the range of musical works expanded. The four-line staff became insufficient for notating more complex and extended melodies.

The fifth line began to appear gradually in the 13th century. Its use became widespread in France in the 16th century and eventually became the standard we know today: the pentagram (from Greek pente, meaning five, and gramma, meaning letter/writing). This five-line staff offered the ideal compromise for notating most vocal and instrumental melodies of the time.

The Challenge of Range: Giant Staves with More Than 10 Lines

At certain times, particularly during the Renaissance and early Baroque periods, staves containing more than five lines were used.

This practice was especially common in notation for keyboard instruments, such as the organ or clavichord, whose range far exceeded that of the human voice. To avoid the excessive use of extra lines, some composers and scribes simply used a single large staff with 8, 10, 11, or sometimes even up to 15 lines to notate the music.

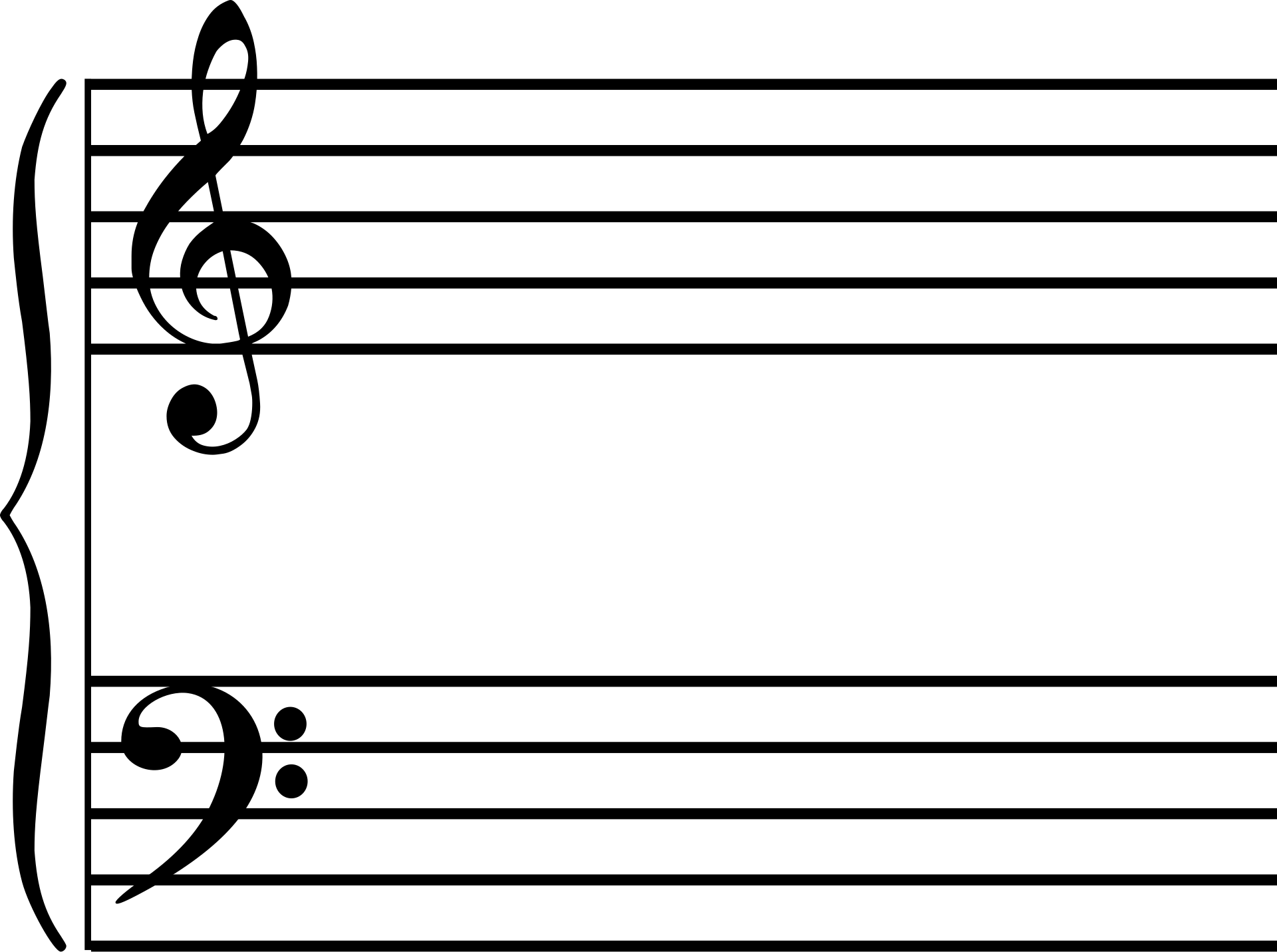

The Grand Staff

Identifying whether a note is on the 7th or 8th line is extremely difficult for the human eye: it requires significant cognitive effort, which greatly slows down sight-reading.

This is why the system we use today for the piano was adopted. It consists of two five-line staves stacked and connected by a brace.

This system proved infinitely more readable and became the standard for the black and white keys of the piano keyboard – but also for the organ, harpsichord, celesta… –, the harp, and other instruments with a wide range. This confirmed that the clarity of the five-line staff was too valuable to give up.

How Many Staves Are on a Sheet of Music?

The number of staves on a sheet of music varies depending on the ensemble. It ranges from a single staff for a solo instrumentalist to much more complex configurations.

A typical score for an acoustic or digital piano uses two staves, but virtuosic works by composers like Albéniz or Rachmaninoff may require three or even four.

The organ always requires three staves to accommodate the pedalboard.

This culminates in a full orchestral score, which contains dozens of staves—one for each instrument or section.